Words were magic – Greenland

Malin Skinnar returned back to Greenland many times. Inspired by the myths she went on tour with her storytelling exhibition.

”A Journey in the Arctic border regions” – includes her illustrations, photos and stories that are inspired by tales and myth.

Published in Scandinavian Public Library Quarterly 2/94

Kalaallit Nunaat – The land of people

I went out over the crust of the snow and was gripped by a desire to pay homage to nature and all the happiness the sea creatures brought people.

Suddenly the mountain rose up against the stars and was about to topple over me. Words lay in the pit of my stomach and I was filled with a strange feeling.

It was as if my own form was not enough, as if words were too small and all the beautiful so endlessly large.

All of a sudden a song came from my breath, and I caught the words and breathed again.

Homewards I went then to my brothers, and we listened to the song that breathed all the night.

The Inuit art of telling stories was theatre in its most intimate form.

Movement, mimicry and symbolism formed a tapestry strong enough to survive for thousands of years among the nomads of the tundra.

For us Europeans, the sagas can seem illogical, with astonishing, often highly grotesque turns.

This can be explained by the life supporting messenger — the saga — constantly being kept alive.

Words took on new forms at the same time as symbols and memories changed costume, all to match the listeners’ need of recognition.

The legend of the Mother of the Sea, the best-known of the mythological forms of the Inuit, is said in some tales to be the wife to the Animal with the Iron Tail — a creature that sought its way with its tail backwards across the ice.

Some believe that this theme of an animal with an iron tail began at a time when mammoths still trod the earth — a creature that has survived orally through tales, but after millennia has become an unintelligible being in the words of the tales.

Perhaps the account of a huge animal’s tail of iron is an interpretation of the mammoth’s immense trunk. These are bewildering thoughts and carry respect for the human ability to preserve experience, knowledge and wisdom from time out of mind.

Not employing the familiar, European phrase of ”Once upon a time . . . ”, the storyteller in Greenland catches listeners’ attention by saying ”This story is so old that no-one knows from whose throat it first came.”

The creator of the legend is said to become visible, and to terrify to death any reteller who added to the tale or subtracted part of it.

The long tales were to alleviate hunger, bring light into darkness — and to maintain hunters’ patience during lengthy waits for prey.

The best teller was the one whose tales listeners never ceased to listen to, whose words caused them to fall asleep!

Words could be given as gifts, or be inherited.

Subject to remarkable rituals, a magic formula could be passed from one man to another: anorak hoods drawn up, back turned to back, high up on a mountain, in a crevice where the sea could not eavesdrop, the donor would intone the formula and the recipient would imitate it, twice, in repetition.

Then the magic words would be transmitted, being effective only for the one who had been seized of the couplet.

To assure himself that his being contained no remaining words of power, the donor would cram his fingers into his throat and cast up what was left!

”People were once aware of the power of words,” related the old East Greenland man, Asineq;

”Words could once caress or like a harpoon, pierce their goal like a whiplash.

A sore from a weapon might burn until it had healed, but a word pleases or wounds for life.

Words have an amazing strength.”

Mask dances resolve conflicts

Of old, when small hunting com- munities could comprise some fifty people, individuals depended entirely on one another and a conflict could be a total catastrophe.

Problems were often resolved through parodic, masked dances or tales, into which the conflict would be gently woven. Tougher problems were resolved through lampoons and drum dances.

The listeners would take sides, for and against whoever might have offended the community, and the loser would be laughed out of the village.

The nomadic life from which the Inuit have descended has refined their tradition of oral narrative.

When on the move, people could have no burden other than the sledge they pulled, the child they carried or the old people who sought support.

Words carried wisdom, and the language was filled with metaphors so that a valuable detailed knowledge should find a firm niche and follow from generation to generation.

Pictorial words

The language of Greenland (polysynthetic) is rich in clear, painterly words that we can represent only with wordy sentences.

Nowadays, the written, rational language of Greenland would be lost in any competition with the briefer, more concise Danish. By contrast, many Greenland writers find their own tongue contains many distinct nuances that European communications lack.

”To translate my texts to Danish or English is to try to describe a painting with codes!” claimed a young poet.

But many try — and succeed with exciting results. In his novel about the Greenland girl, Smilla, the Danish novelist, Peter Hoeg, describes part of the ”language of Greenland as a union of space, movement and time that is self-evident for Eskimos but cannot be reproduced in any everyday European language.”

The Inuit of Greenland are said to belong to the group of native people that has come furthest in their pursuit of the right to decide for them- selves over their future.

Since 1979, when Home Rule for Greenland was introduced by the Danish parliament, the language of Greenland has lived through a rebirth, having been accorded formal equality with Danish.

In the capital of Nuuk, on the west coast, the attitude changed during the 80:th and spreed native power all over Greenland.

Everything is there, all going on and at once — kayaks, science, seal hunters and hiphopers, one as usual as another.

At present an exclusive fusion of culture are bearing fruit, after the early ears of an arctic revolution.

Artists and musicians boldly mix the throat songs with distorted guitars, and actors find inspiration in the timeless stories and myths of the island. It´s very interesting and inspiring.

Dance of life

An actress, Laila Hanssen, works much with children. In many performances she uses the former ritual mask dance. It has three elements: the clown, the rite of fertility and the revelation of the child’s fear.

The dance is about life as a whole and can express the hard, whipping of the hurricane wind or the terror felt on coming face to face with a polar bear.

Once it was possible to train children in the ability to cope with fear.

The surprising movements of the grotesque mask dance should offer them the possibility of being frightened under secure circumstances at a moment of danger in the wilderness, when a decision would bring life or death, the child was trained to act rather than to be paralysed.

Sagas now are not really suited to the modern, contradictory Greenland.

”Eeeeemiliooop” cry the laughing children at the daycare centre when they learn that I am Swedish. Astrid Lindgren’s Emil in Lönneberga has come to live on the tundra, with chickens, and cows, and little Ida’s summer song.

The tale of the Mother of the Sea has perhaps been used as far as it can be, but actor-work on, dramatising their inherited culture and searching deeper into the treasures of the sagas.

Laila sometimes stands in at daycare centres, and says that she can scarcely come through the door before the children beg her to tell stories.

”The kids sit as if bewitched for hours, listening.”

The Greenland sagas are often complicated, with surprising turns and abrupt resolutions. Laila considers that the sagas that are brutal help children to expose their fear in the presence of others.

”Children nowadays are over-protected and lack the excitement that nature offers. Our tales have changes as unexpected as the unpredictable nature of the Arctic. I believe that they learn their country through the sagas and themselves through myths.”

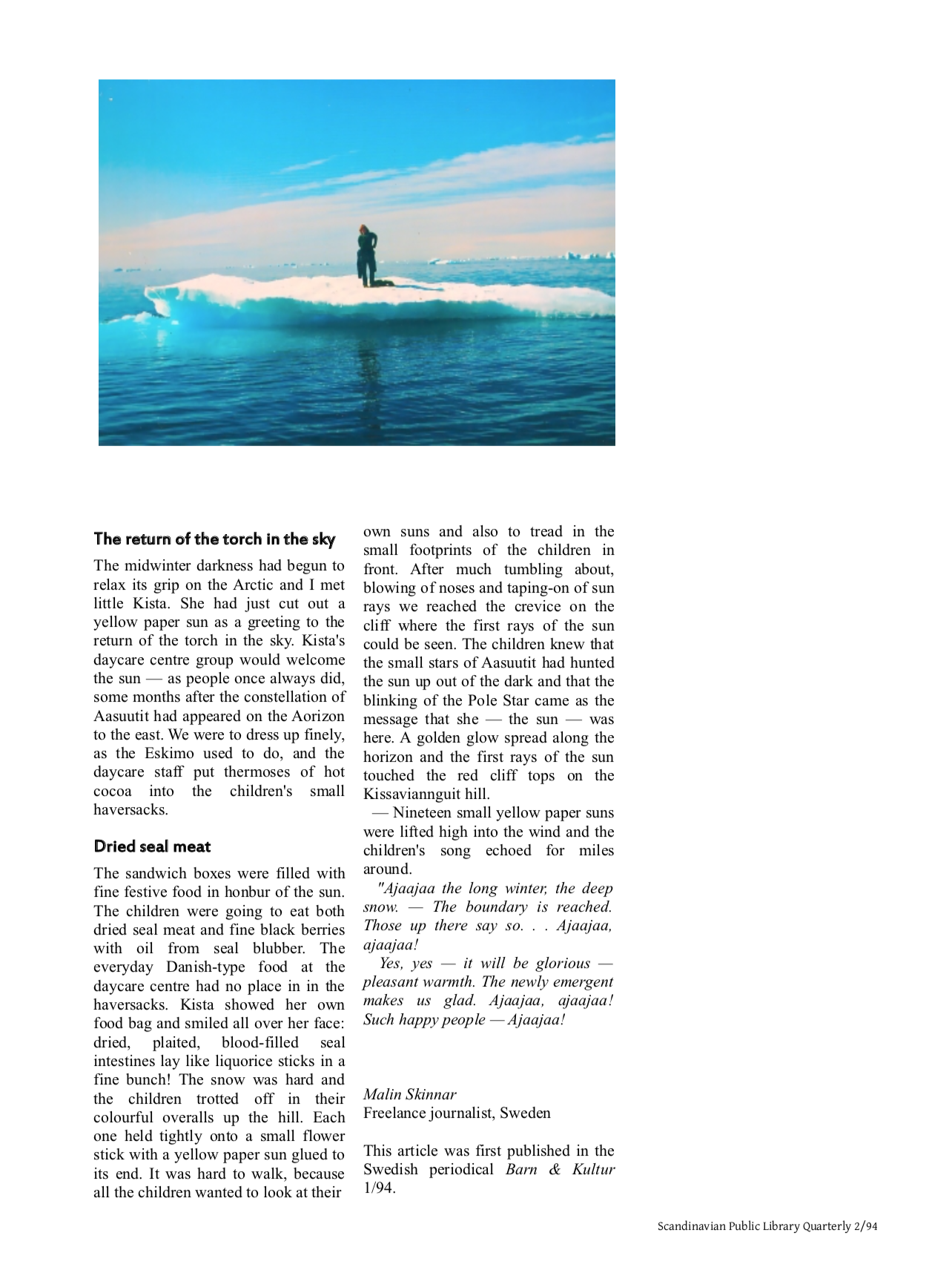

The return of the torch in the sky

The midwinter darkness had begun to relax its grip on the Arctic and I met little Kista.

She had just cut out a yellow paper sun as a greeting to the return of the torch in the sky.

Kista’s daycare centre group would welcome the sun — as people once always did, some months after the constellation of Aasuutit had appeared on the horizon to the east.

We were to dress up finely, as the Inuits used to do, and the daycare staff put thermoses of hot cocoa into the children’s small haversacks.

Dried seal meat

The sandwich boxes were filled with fine festive food in honbur of the sun.

The children were going to eat both dried seal meat and fine black berries with oil from seal blubber.

The everyday Danish-type food at the daycare centre had no place in in the haversacks.

Kista showed her own food bag and smiled all over her face: dried, plaited, blood-filled seal intestines lay like liquorice sticks in a fine bunch!

The snow was hard and the children trotted off in their colourful overalls up the hill. Each one held tightly onto a small flower stick with a yellow paper sun glued to its end.

It was hard to walk, because all the children wanted to look at their own suns and also to tread in the small footprints of the children in front.

After much tumbling about, blowing of noses and taping-on of sun rays we reached the crevice on the cliff where the first rays of the sun could be seen. The children knew that the small stars of Aasuutit had hunted the sun up out of the dark and that the blinking of the Pole Star came as the message that she — the sun — was here.

A golden glow spread along the horizon and the first rays of the sun touched the red cliff tops on the Kissaviannguit hill.

— Nineteen small yellow paper suns were lifted high into the wind and the children’s song echoed for miles around.

”Ajaajaa the long winter, the deep snow. — The boundary is reached. Those up there say so. . . Ajaajaa, ajaajaa!

Yes, yes — it will be glorious — pleasant warmth. The newly emergent makes us glad. Ajaajaa, ajaajaa! Such happy people — Ajaajaa!

Yes, yes — it will be glorious — pleasant warmth. The rising sun makes us glad. Ajaajaa, ajaajaa! Such happy people — Ajaajaa!

Story, paintings and photo by Malin Skinnar storyteller, Sweden

This article was first published in the Swedish periodical Barn & Kultur 1/94.