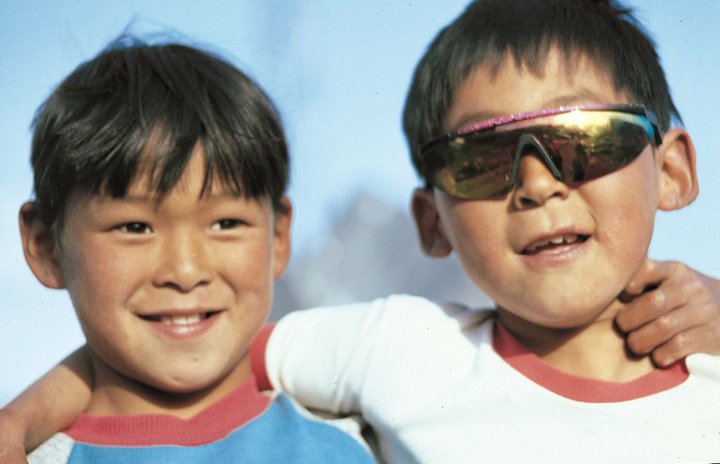

Valen tittade på mig – Grönland

Valen dök upp och tittade på mig under kajaken

Hör om späckhuggarmötet på Grönland. Om att hantera livet i naturen och att klara sig själv mitt i universum. Och bästa knepet för att få varma fingrar.

Berättat under en kajaktur på Ljusnan när jag färdades med husbilen genom Härjedalen.

Hör berättelsen

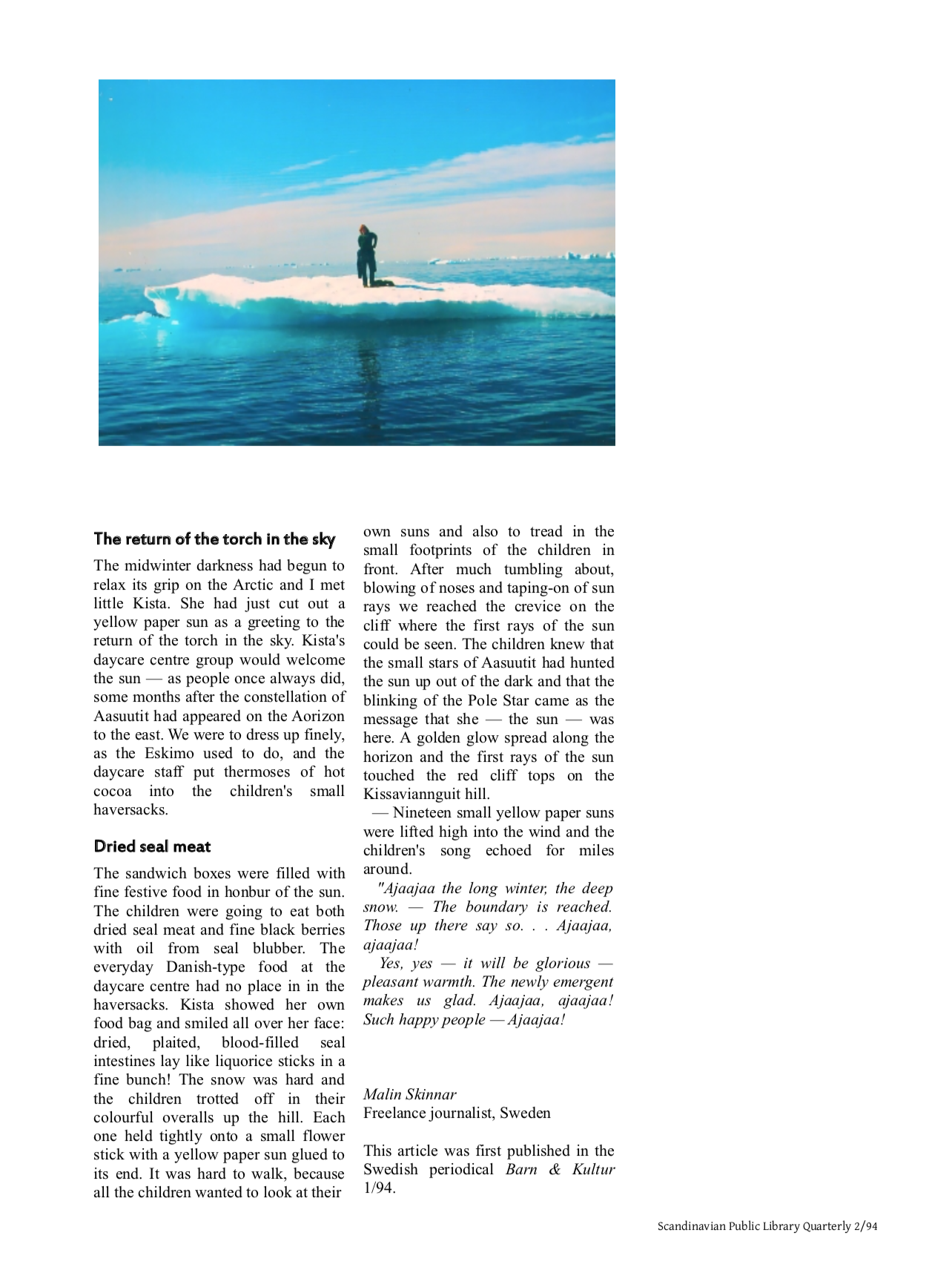

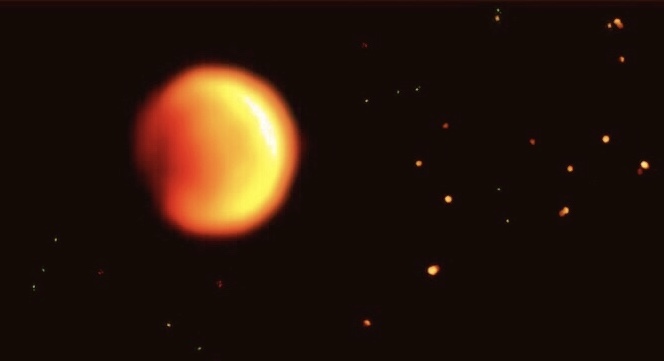

Stor som ett urtidsdjur reser hon sig ur klippblock och is – inslandsisen. Med ett muller kraftigare än tordön, släpper hon sitt innanmäte i havet – ännu ett isberg i fjorden – jordens svalka.

Vi paddlade och spejade – allt levde – hav, himmel och is. En morgon då fjorden höjde och sänkte sig som en jättelik lunga efter nattens orkan, gled våra kajaker fram bland ytterskärens drivis. Vi paddlade in mellan två höga isberg där luften svalnade.

Ljudet av paddeln ekade mellan de två branta isväggarna. En ring vidgade sig på ytan framför kajaken, blev dubbel och sprack som en bubbla. Mitt hjärta slog fortare och fortare. Ur havet reste sig en gråskimrande kropp likt en vågbölja som följde kajaken.

– En val!

Tanken på den tunna vattenytan och den stora kroppen som simmade omkring mig, gjorde mig andlös.

Valen sjönk men kom kort därefter upp på andra sidan, välte kroppen mot solen och försvann.

– Valen hade sökt sig upp ur djupen för att se vem som plaskade på hans himmel.

Då kände jag mig som människorna där alltid måste ha känt sig inför naturkrafterna. Jag var mindre än allting runtomkring mig men varken viktig eller oviktig, bara en del av alltihop. En människa som måste skapa min stund på jorden men ändå fri att ingå i livets rytm.

Det som sker det sker när man färdas genom livet på ett klot i ett hav av stjärnor.

Grunden till de gamla myterna och berättelserna om mod och styrka kunde för mig inte åskådliggöras på ett klarare sätt.

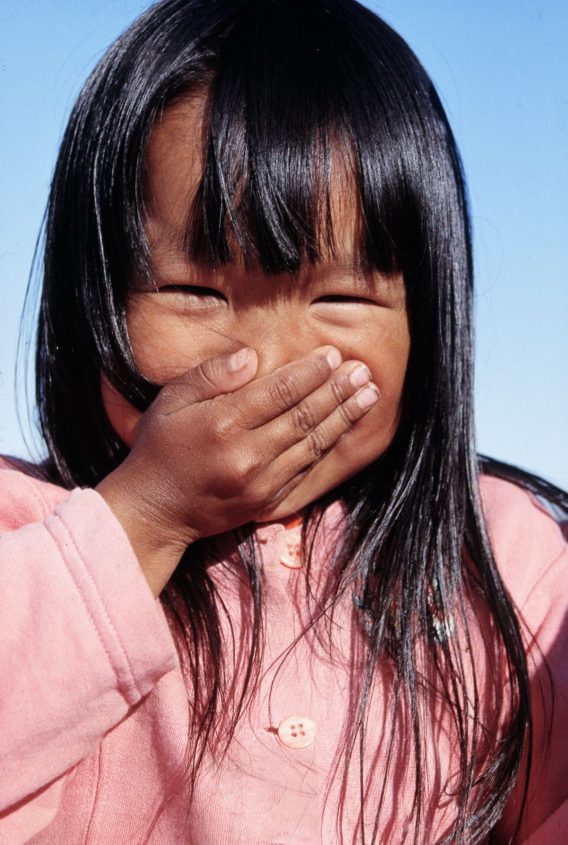

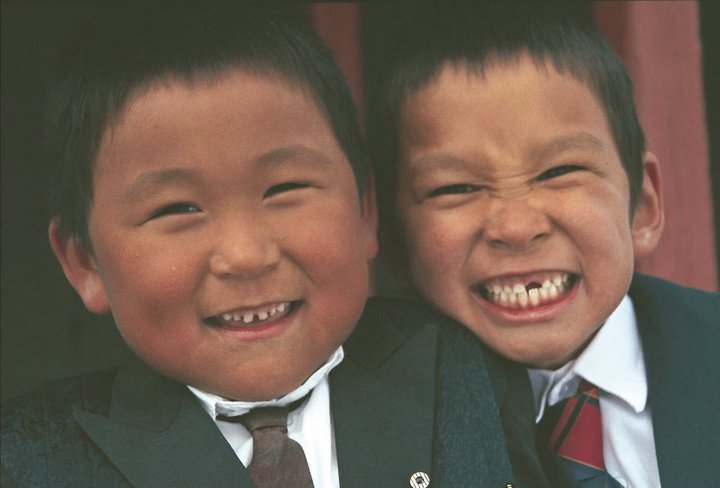

Jag fascinerades av hur naturen präglat människorna och den kultur de skapat kring de arktiska livsvillkoren.

Naturkrafterna gör sig ständigt påminda och tillåter människan att bara vara. .. att bara vara med.

– Silarsuaq kisimi naalaagavoq – Naturen är vår härskare, som en jägare sa då stormen äntligen bedarrat.

Under nittotalet vistades jag på Grönland en stor del av mitt liv. Under elva expeditionslika resor färdades jag längs med kusterna och levde med jägare och hårdrockare, hiphopare och forskare i ytterbygderna.

Denna berättelse finns i sagoboken jag skrev om Kuitse – Pojken som blev stark som en isbjörn. Läs mer av mina Grönlandsberättelser här.

TV 4 – 1994 ; jag berättar om Grönland

Här är hela visan från inslaget ovan